Monty Don, the nation’s gardener, has a bit of a bee in his

bonnet about begonias. A rather

longstanding

(article from 2000, and there are

others

since then) and particularly buzzy bee at that. Reading the article from 2000,

he’s not keen on houseplants, either.

I was going to let it go. Each to their own, etc. We all have

likes and dislikes. Obviously, what I like is right, and what you like is

wrong, but I will allow you to grow it in your own garden. However, when ‘the

nation’s gardener’ (how Monty might be viewed, having the ear of the national

press and a weekly BBC2 gardening show) sweepingly dismisses not just one genus

(for there are lots of types of begonias) but also a way of gardening (tender bedding

– how ‘common’), then I think it begs a little closer examination.

Perhaps I am reading too much into this, but when the

article from 2000 contains the following quote, I feel we are starting to touch

on my discomfort with Monty’s views:

“The honest truth is that I think if I really had no

garden - no possibility of an

allotment, no little yard, however dingy - I would

forgo house plants and buy

cut flowers daily. When we lived in London, I would

often go and cut a bunch of

flowers from the garden to take as a present when

going to friends for dinner. “

So there we have it. If Monty could imagine living in a

squalid hole with no outside space, no rolling acres of pleached hedges and box

and views to the countryside, no wildflower garden with writer’s shed, no

glasshouses, he would buy flowers on a daily basis. That’s great. He would be

lucky that he can do that. Perhaps, however, some of those people who do live in houses or flats with

or without a dingy little yard cannot afford a couple of pounds a day, or even

a month, on fresh flowers (and we can be pretty sure that Monty wouldn’t be

buying a couple-of-quid bunch of daffs from the local supermarket).

Perhaps, just perhaps, a few quid spent on begonia tubers, and a six-pack of trailing lobelia, and you

have a summer of bright, vibrant colour. Goodness, sometimes you can even

coordinate the colours of these flowers, as heaven forfend that we have a bit

of colour clash. I mustn’t be too harsh on Monty, as one reason he scorns the

tender bedding is that it is often sold too soon and can end up curling up its

toes if planted out too early. But his attack on such bedding is more than

that, and perhaps I’m over-analysing this, but to me it relates to class and

taste.

I’ve been reading quite a lot about

Pierre Bourdieu

recently. Primarily because I’m writing an 8000 word essay on how his concepts relate

to student choice in higher education. How does this link to begonias? Well,

Bourdieu explored a lot about class, and ‘reproduction in society’ – how it is

that those with power and influence maintain that power and influence, and

those without stay without (with a few minor exceptions). One area he explored,

particularly in his book Distinction, is taste and culture. What is good taste,

how society view taste, how the concept of ‘good taste’ is maintained (forgive

me if this is a bit of a rubbish explanation – I’m still grappling with his

theories).

What Bourdieu suggested is that taste is ingrained within

our social place in society. We have class-based predispositions to taste,

based on what we absorbed through our upbringing and social setting. I was

brought up in an initially working-class environment. My household, my friends’

households, didn’t grow up listening to classical music, going to plays,

visiting museums. Whilst I don’t know much of

Montague Don’s background,

it would appear that he had a different, established middle class, upbringing

from me, attending various private schools and Cambridge University. He had

different experiences of taste within his upbringing. According to Bourdieu, in

this established middle-class upbringing, he will have developed greater

cultural capital.

Capital forms the foundation of social life, according to

Bourdieu. There are several types of capital - the one most easy for us to

understand is perhaps economic capital – those with more economic capital are

those with more money. Cultural capital is composed of the symbolic elements that

one acquires as part of a particular class – the mannerisms, skills, behaviours

and, importantly here,

tastes that a particular class

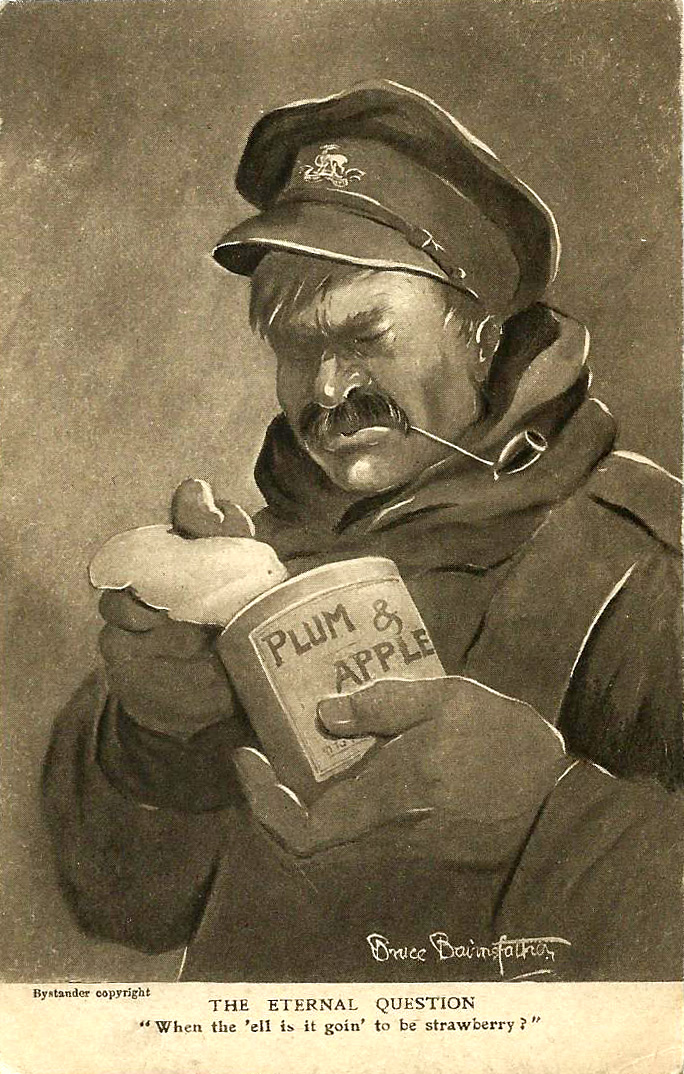

shares. Those with greater cultural capital can buy

something

like this because it is kitsch and makes us laugh knowingly and ironically

(always with that understanding that someone inferior actually likes that stuff

– the humour is there because we see ourselves as superior to the person who

buys it without irony). Someone with a bit less cultural capital would scorn it

as hideous. But to someone with even less cultural capital, it is a pretty and

useful part of the household decoration, and not a piece of ironic kitsch.

So, begonias. Very much like a frilly toilet roll cover.

Bright, flouncy, often in clashing colour schemes. Abhorrent to the good taste

of the middle classes. The middle classes who can choose to have bright

colours, but instead talk about their deep, rich, jewel-like hues:

"It's a

gesture against all that pastel good taste," says Monty Don. "The

cottage-garden

style has gone as

far as it can and disappeared up its own backside."

Ahh, the pastel good taste of the cottage garden of the

1990s has been replaced in the middle-class hierarchy of cultural capital by

jewel-like colours. Not garish. No, instead rich, sumptuous colours.

This

begonia looks pretty rich, jewel-like and sumptuous to me. But it’s frilly.

It’s a tender annual. The working class buy them to plonk in the ground:

No expert knowledge needed for these. No understanding of

garden design or complex horticultural growing conditions. Anyone can grow them

– even those people (the working class) with no taste, no back yard (however

dingy), just a pretty basket

possibly

shaped like a puppy (bought non-ironically). How common.

If not begonias, it would be some other form of plant or

gardening practice. Take pelargoniums. I’m not saying Monty doesn’t adore the

zonal

pelargonium bedding display. But many,

perhaps

middle class, keen gardeners would not give them the time of day, and instead

would rave about the beauty of

Pelargonium

ardens – to many non-horticulturalists a rather sparsely flowering and

nondescript plant. But, if you have a bit of cultural capital, you can expound

on the simplicity of the flowers, the richness of the colour, the ‘natural

beauty’ of it, compared the cheap, common, blousy bedding pelargonium.

So, let’s not be snobby about plants. Let’s not be snobby

about people who grow plants, even if they buy them ready-formed and

bung

them in a bog (and we’re not talking the sort of bog Rodgersias thrive in).

You might

abhor

the meerkat, but some adore it.

Celebrate everyone’s taste, and make a little room in your

life for begonias. Or maybe I've just read a little bit too much into this... what do you think?